Deploying CMMC 2.0 model to enhance defense industrial base cybersecurity against evolving threats

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) released in November the CMMC 2.0 model, an upgrade of its earlier 1.0 framework, covers cyber protection standards across the defense industrial base (DIB) from evolving threats. The Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) framework has been developed to protect sensitive unclassified information that is shared by the DoD with its contractors and subcontractors.

The defense sector is particularly sensitive to perils posed by nation-state adversaries, ransomware attacks, and other security vulnerabilities. Sensitive information can be exfiltrated or stolen, access to information systems may be denied, and there is the risk that malicious hackers will corrupt data and compromise the operation of IT, as well as operational technology (OT) systems.

The CMMC 2.0 model helps reduce costs, especially for small businesses, improves trust in the CMMC assessment ecosystem, and clarifies and aligns cybersecurity requirements to other federal requirements and commonly accepted standards.

Once the CMMC 2.0 model is implemented, DoD will specify the required CMMC level in the solicitation and in any Requests for Information (RFIs), if utilized. The federal agency also said that if contractors and subcontractors are handling the same type of Federal Contract Information (FCI) and Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI), then the same CMMC level will apply. In cases, where the prime contractor only flows down select information, a lower CMMC level may apply to the sub-contractor.

FCI means that information, not intended for public release, which is provided by or generated for the government under a contract to develop or deliver a product or service to the government, but not including information provided by the government to the public, while CUI refers to that information that requires safeguarding or dissemination controls pursuant to and consistent with applicable law, regulations, and government-wide policies but is not classified under Executive Order 13526 or the Atomic Energy Act, as amended.

Industrial Cyber reached out to experts to gauge from them exactly how the requirements of the CMMC 2.0 model are different from that of version 1.0, while taking into account what these changes mean for defense contractors and the DIB.

The majority of the requirements remain unchanged under CMMC 2.0, Jacob Horne, chief security evangelist at Summit7, told Industrial Cyber. “Organizations with Federal Contract Information (FCI) must still implement the security requirements from the clause FAR 52.204-21. Organizations with Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) must implement the security requirements in NIST SP 800-171,” he added.

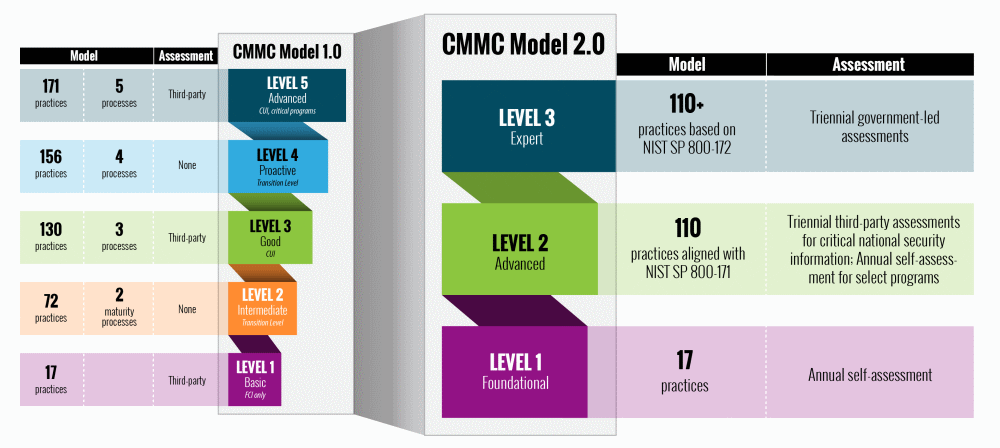

Select organizations with highly sensitive information must implement a subset of requirements from NIST SP 800-172, according to Horne. “These requirements represent CMMC 1.0 levels one, three, and five, respectively. CMMC 2.0 removed levels two and four, which were never intended to be used as formal contract requirements. CMMC 2.0 also removed twenty CMMC-unique requirements for CUI holders, although it is expected that those requirements will return in the future under a revision to NIST SP 800-171,” he added.

While the substance of the requirements remains mostly unchanged, program-level changes such as allowances for temporary deficiencies, limited waivers, and external assessments only for certain CUI holders were new for CMMC 2.0, Horne said. “As such, defense contractors still face essentially the same security requirements they did before.”

CMMC 1.0 envisioned that as many as 300,000 defense supplier companies, who have either CUI or FCI, would be subject to mandatory third-party assessment and would not be eligible for DoD contracts unless they received a ‘certification’ for perfect accomplishment of applicable cyber standards, Robert Metzger, an attorney based in Washington D.C., who is also an expert in cyber, supply chain and national security areas, told Industrial Cyber.

CMMC 2.0 is much less ambitious, according to Metzger. Only a fraction of ‘Level 2’ companies, who have CUI with military mission significance, would be subject to third-party assessment, he added.

“Companies with just FCI would self-assess, report their scores to DoD, and be subject to an annual ‘affirmation’ by a senior executive,” Metzger said. “Also important is that CMMC 2.0 permits DoD to accept Level 2 assessment results even if there are some gaps yet to fill in their security. Finally, CMMC 2.0 pushes off, for a year or more, the date when companies will be subject to solicitation or contract clauses that require CMMC compliance,” he added.

CMMC 2.0 makes a number of changes that will come into force through the federal rule-making process, Vincent Scott, CEO of Defense Cybersecurity Group, a cyber consulting company focused on DoD cyber requirements for the DIB, told Industrial Cyber. “Some of those changes we have written references for today via the assessment and scoping guides, and others the DoD has discussed but we have not seen a specific written regulatory example.”

Scott said that based on what the DoD has stated publicly to date these changes when in force will include elimination of the ‘Delta 20’ controls/practices/security requirements contained in CMMC 1.0, removal of the process maturity requirements, a reduction from a five-tier system of certification to a three-tier system of certification, and change from all contractors being assessed independently to a subset of the Level 2 contractors, and the formal designation of DIBCAC (Defense Industrial Base Cybersecurity Assessment Center), as the organization that will conduct the new Level 3/old Level 5 assessments. He also flagged the modification of self-assessment requirements from triennially, as currently called for in DFAR 7019/7020, to annually and the addition of a self-assessment requirement for all contractors at Level 1.

Pointing out that not all contractors will be assessed, Scott said “those who only handle FCI will be an L1 self-assessment, and those who handle CUI will either be self-assessed or have an independent assessment from an authorized C3PAO at Level 2 (old Level 3). We do not know for sure which companies will fall into which categories, but the DoD has made public comments that those involved directly in weapons system production will likely be candidates for C3PAO assessments.”

The CMMC 2.0 model will not be a contractual requirement until the DoD completes rulemaking to implement the program, which is likely to take between nine to 24 months. CMMC 2.0 model will become a contract requirement once such rulemaking is completed.

DoD contractors with DFARS clause 252.204-7012 in their contracts have cybersecurity incident reporting requirements outside of the CMMC program, Horne pointed out. “Fundamentally, CMMC is an assessment and certification program that seeks to verify contractor implementation of the security requirements in NIST SP 800-171,” he added.

The clause DFARS 252.204-7012 prescribes contractors to implement those requirements, according to Horne. “In addition, the clause requires incident reporting, data retention, and other actions to facilitate DoD forensic investigation. These obligations have existed for years – well before CMMC started to come together – and will govern incident reporting for DoD contractors during the interim period and after CMMC is a formal requirement,” he added.

Under the current regulation, the requirements for incident response and reporting to the DoD have actually not been impacted at all in this, Scott said. “DFAR 7012 lays out cyber incident reporting requirements.”

From a general perspective, “all DoD contractors should be familiar with the DIBNET portal, where incidents are to be reported, they should have at least one employee registered with the site and in possession of a medium assurance token to allow for expeditious reporting when an incident occurs, and they should be availing themselves of the free threat intelligence available to every DIB company with a facility clearance,” Scott added.

CMMC 2.0 doesn’t change cyber requirements already in place, Metzger said. “The DFARS 252.204-7012 ‘Safeguarding’ clause requires DIB companies to provide ‘adequate security’ relying upon NIST SP 800-171. Those obligations are unchanged – and they include specific cyber incident reporting requirements. Companies are required to ‘rapidly report’ cyber incidents, within 72 hours of discovery, and to support DoD forensic and follow-up activity. Since the -7012 rule first went into place, companies should be aware that the federal government places much more emphasis upon incident reporting,” he added.

Legislation is under consideration that would mandate reporting by more companies and in more circumstances, according to Metzger. “ The purpose of reporting is not just ‘damage assessment’ but also to help the federal government understand the attack vectors and methods – and hopefully help other companies avoid, mitigate, or recover from such attacks. For many reasons, including the proliferation of ransomware attacks, DIB companies should be prepared to identify an attack and rapidly respond, report, and recover,” he added.

To deal with its international partners, the DoD has chosen to establish agreements related to cybersecurity and count on these non-US partners to safeguard sensitive national security information.

“It’s important to remember that NIST SP 800-171 is the core of CMMC 2.0 level 2,” Horne said. “That is, the 110 NIST controls in NIST SP 800-171 represent the minimum baseline for the protection of CUI. There are many categories of CUI, but not all forms of CUI have export control restrictions such as ITAR or EAR data.”

If stricter requirements above the minimum baseline are required for any reason, then it is the domain of ‘CUI specified’ protections such as ITAR, not the domain of NIST SP 800-171 and CMMC, Horne added.

“First, there is no other way than ‘by established agreements’ to deal with international partners. International partners are not subject to US law or regulation and mutual agreement is the sole avenue to address concerns with international companies,” Scott said. “Second cyber has been evolving rapidly. Much more rapidly than government policy and regulation. Finally, let’s put our own house in order before directing someone else to put their house in order. This could start and should start with the DoD following its own rules on CUI,” he added.

The entire cyber structure is built around securing the confidentiality of CUI, yet the DoD continues to grossly and willfully abrogate their responsibility, as written in regulation and their own instruction (DoDI 5200.48) to properly mark CUI, and clearly tell contractors what is and is not CUI in their contracts, according to Scott. “As far behind as the Defense Industrial Base is in implementing the required technical controls, the DoD is behind in implementing their own use of CUI marking. In order for this to make a difference, and actually better protect the DoD’s information, they MUST drive training and awareness and use of the CUI marking system down to the lowest levels of the DoD,” he added.

Scott pointed out that contractors require leadership on this. “They look to their day-to-day customers to provide them guidance and tell them what to do. If those contracting officers, contracting officer technical representatives, and PM’s are not giving any guidance or worse, as is too often the case, they are giving guidance that is counter to the governing regulations then contractors will struggle to properly implement the CUI protection that the DoD is looking for,” he added.

The U.S. exports billions of dollars of military equipment to allies and partner nations, so it isn’t surprising that our foreign contractors seek to sell to DoD, according to Metzger. “Export controls limit the access of non-U.S. persons to sensitive technology. Application of U.S. cyber rules to foreign sources presents complications. Foreign sovereigns have their own methods for cyber security and may resist or reject U.S. standards. DoD has negotiated cyber security arrangements with only some countries,” he added.

U.S. defense contractors typically have methods to assess potential foreign participants in their supply chain and use contractual arrangements to protect sensitive information, Metzger said. “Emerging technical – such as ‘virtual desktop infrastructure’ – can limit access to and use of CUI by foreign suppliers. The prevailing view is that U.S. security is stronger by reason of our use of foreign sources. But there is pressure in many areas of industry and technology to ‘re-shore’ capabilities to the U.S. and reduce foreign dependencies,” he concluded.