DGAP works on mapping critical infrastructure sectors to deliver global consensus, propel UN cyber discussions

The German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) published a paper examining the policy documents of 193 United Nations member states and Taiwan. It analyzes what countries perceive as critical infrastructure. While it may at first appear clear what critical infrastructure sectors are, this view varies by member state. By mapping what countries designate as their critical infrastructure sectors, the DGAP document hopes to propel U.N. cyber discussions, which have so far been slow to result in agreement on a global common denominator for critical infrastructure sectors.

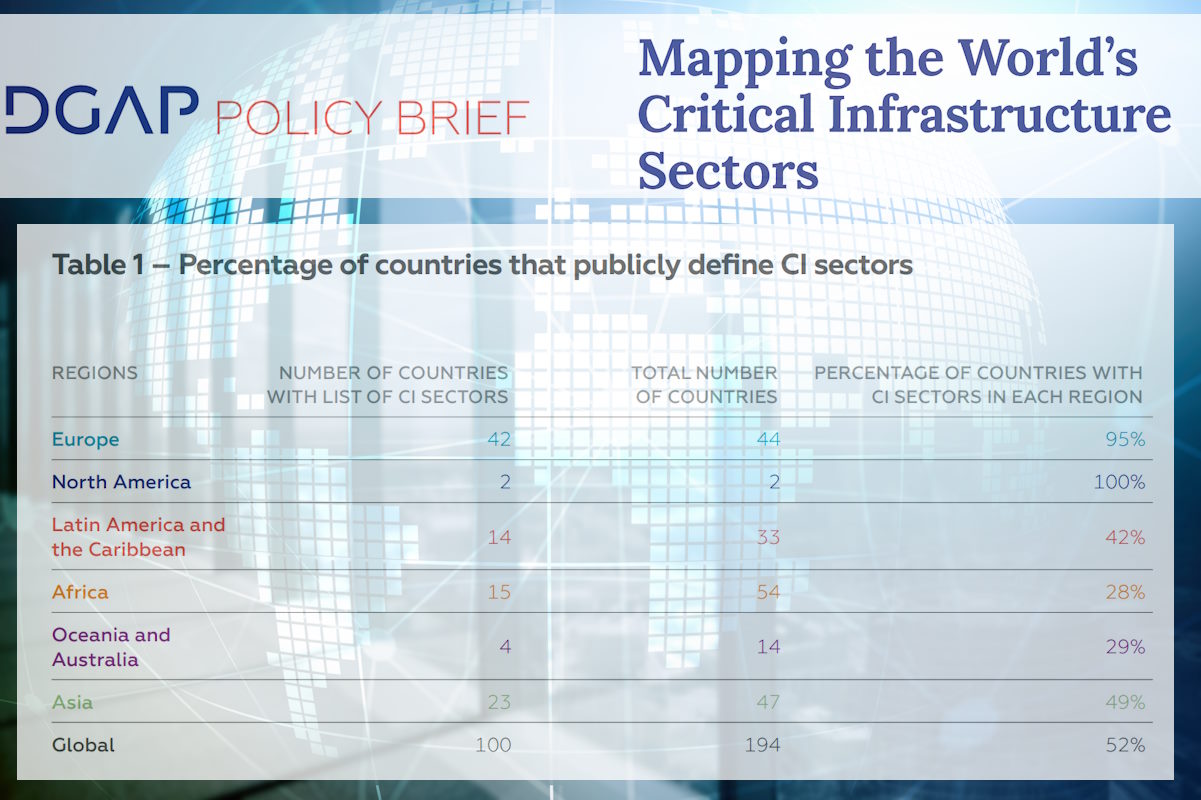

Titled ‘Mapping the World’s Critical Infrastructure Sectors,’ the paper disclosed that 100 of 194 countries have published what they perceive as critical infrastructure sectors. The critical infrastructure sectors that countries most frequently mention are energy (96 percent), information and communications technology (ICT) (95 percent), transport (93 percent), economy and finance (89 percent), public services (84 percent), and health (83 percent). By far the least-mentioned categories worldwide are research and education (15 percent), national security (45 percent), food (51 percent), and water (76 percent).

“If it were only a numbers game, the most common CI could be included in a global definition. A more inclusive approach would name all the above sectors as CI at the UN,” Valentin Weber, Maria Pericàs Riera, and Emma Laumann wrote in the DGAP paper. “Many countries need further support in defining CI. While almost all countries in Europe and North America define CI sectors, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania are far behind.”

The DGAP is committed to promoting foreign and security policy at both the German and European levels, with a focus on democracy, peace, and the rule of law. DGAP’s team of experts offers advice to decision-makers in politics, business, and civil society, drawing on their extensive research in foreign policy. Additionally, it provides training programs for young professionals in international leadership, aiming to cultivate future leaders in the field.

By facilitating well-informed foreign policy decisions, fostering informed debates on foreign policy matters in Germany, and advancing German expertise in this area, DGAP strives to make a significant contribution to the field of foreign policy.

The DGAP document revealed that more than half of the countries worldwide have an official list that defines national CI sectors. However, a closer look shows that the way critical infrastructure sectors are described varies among regions. In Europe, 95 percent (42/44) of the countries studied have an established list. In North America, which includes Canada and the United States, 100 percent have such a list, while only 42 percent (14/33) of those in Latin America and the Caribbean do. Asia comes in at 49 percent (23/47) and Oceania at 29 percent (4/14).

The region where the fewest countries have a list of definitions is Africa, with 28 percent (15/54). Several African countries have not yet defined their specific critical sectors and are aiming to do so in the coming years. Often these aims are part of the effort to draft and implement a national cybersecurity strategy. Mauritania is one such example.

The objective of the paper is to facilitate the process of reaching a global consensus on critical infrastructure. By mapping what countries designate as their critical infrastructure sectors, “we hope to propel UN cyber discussions, which have so far been slow to result in agreement on a global common denominator for critical infrastructure sectors,” the authors identified.

Built on its previous paper that focused on the cyber context and on deepening the UN norm on not attacking critical infrastructure, the latest DGAP document takes a complementary and broader approach and works to create “a global database with countries’ different definitions of sectors they perceive as CI. While not all countries have an official document laying out their CI sectors, 100 countries do. This allows us to analyze which sectors appear quite often and which do not. It also permits us to compare which sectors are perceived as CI in various regions of the world and, finally, to find similarities across countries,” it added.

It is crucial to establish a common global denominator as to what is or is not critical infrastructure, the authors said. “States are bound under international law not to attack CI (in and outside cyber-space) and have also agreed on a voluntary, non-binding norm on refraining from malicious information and communications technology (ICT) activity against CI in cyberspace during peacetime. Thus, knowing what other states perceive as CI is important to reduce the likelihood of misperception and escalation.”

The DGAP paper identified that while all critical infrastructure is off-limits for both cyber- and conventional attacks in peacetime according to international law, critical infrastructure in cyberspace needs additional protection.

They emphasized that this paper addresses the cyber diplomacy community’s objective of safeguarding critical infrastructure from cyberattacks. However, its relevance extends beyond this community. In today’s interconnected world, where the offline and online realms have converged, establishing a global and shared definition of critical infrastructure holds value for policymakers outside the cyber domain.

It is important to recognize that every sector of critical infrastructure is somehow connected to the internet, making it imperative to address the protection of critical infrastructure from both cyber and conventional attacks as a unified effort. Notably, there has been no significant endeavor within UN cyber negotiations to establish a comprehensive definition of critical infrastructure.

“Current definitions at the UN OEWG on international cybersecurity have been quite arbitrary and have changed over time,” the authors identified. “They have also not striven to be comprehensive. So no process is in place yet that would try to assemble countries’ definitions of CI sectors. This may be because some countries fear that anything that falls outside their CI definition could become a target for cyber operations.”

However, this is misguided, the authors wrote. “This paper does not suggest that the Bahamas, Bolivia, or Madagascar should publish detailed lists of where critical water supply networks or industry facilities lie. This paper rather aims to nudge countries toward publicly naming broad lists of CI sectors that would be abstract and would not provide concrete targets.”

Furthermore, countries publicly listing their critical infrastructure sectors have not been more frequently attacked than those that have not yet defined critical infrastructure, the DGAP paper disclosed. “To the contrary, countries that have codified CI sectors have been better at establishing measures to protect CI. The European Union’s NIS and NIS2 directives are examples of such regulations that improve CI protection. Without a definition of CI, protection is not possible,” it added.

Past and current U.N. processes usually aim to find consensus on a certain topic by encouraging countries to submit their national views – e.g., on international law or progress in securing CI – to a UN platform or to voice them when diplomats gather for substantial sessions of U.N. working groups. In this vein, it took more than a decade to define a norm calling for countries to refrain from attacking CI through cyber means. This paper aims to speed up the process of arriving at a global and common understanding of critical infrastructure.

In conclusion, the DGAP paper identified a couple of main conclusions that can be drawn from this analysis.

First, many countries, particularly in Asia and Africa, are still working on the categorization of their critical infrastructure sectors. While this trend shows a growing awareness of the importance of safeguarding vital systems, it also reflects that 94 countries still have not defined their critical infrastructure sectors nor have response plans to protect them. It is the international community’s task to support those member states in defining and protecting their critical infrastructure.

Second, the authors disclosed that the efforts of countries that have already defined their CI sectors can help foster a common global alignment. “While each nation may have specific needs, the pursuit of a common global understanding of CI could result in significant benefits. Such an approach could lead to improved international cooperation, information sharing, and the development of best practices for protecting CI on a global scale,” they added.

The policy brief answered the ‘what’ questions of critical infrastructure: what countries define critical infrastructure and what those definitions look like. “This is especially useful to gain an understanding of what countries mean by broad terms such as ICT. Some countries say it is submarine cables, others satellite communication; for Russia, it is Russian legal entities and individual entrepreneurs who own information systems; for others, it is broadcast media or the digital economy,” it added.

The variety of definitions captured in this paper is even broader when it comes to public services, encompassing everything from sensitive organizations to urban areas, national monuments, and values. A key goal in writing this DGAP paper was to go beyond assumptions as to what critical infrastructure is and to provide facts, the authors identified. Countries can use the global overview to add critical infrastructure sectors they have omitted, but which other countries have on their lists, and exchange information with them as to how to best protect those sectors.

“But there is more to studying CI than compiling what countries perceive as CI. There are many more ‘why and how’ questions for future research,” according to the DGAP paper. “Why do countries publish CI lists at a certain point in time? Is it because they have been attacked recently and need to double down on CI protection?”

They pointed out that Australia, for instance, added telecommunications companies to its existing list of critical infrastructure in 2023. “This was a direct reaction to a large hack telecommunications companies in Australia suffered in 2022. Adding telecommunications companies to the list of CIs not only puts ink on paper, it also creates new rules with stricter security procedures for this CI sector, which will be enforced by the Australian government.”

While the authors chose not to study those that have not codified critical infrastructure, one explanation for the lack of codification may be that many countries simply do not have the resources to establish critical infrastructure regulation. It might also be that certain regional organizations have not been nudging countries in this direction, as for example, the EU has done.

Another question for future research is, for example, why certain countries include national security in their strategies and why others omit food or water.

Many of these questions may be answered by further research. But alongside in-depth analyses by researchers, states themselves should also establish their own initiatives, the authors said. Those that have published their lists of critical infrastructure sectors should push for global standards regarding critical infrastructure definitions and critical infrastructure protection. As they have already set standards by publishing lists, they have a first-mover advantage and could decisively shape global discussions on this issue, they added.